Bike With A Motor For Sale Vs Regular Ebike: What’s The Difference?

Introduction: More Than Just a Motor

If you're searching for a "bike with a motor for sale," you've entered a world of exciting but often confusing options. The term itself can mean two very different things. On one hand, you have the DIY bike with a motor, typically a standard bicycle modified with a gas or high-powered electric kit. On the other, you have the modern, factory-built regular e-bike, an integrated and legally regulated machine.

These are not interchangeable. They differ drastically in technology, legality, riding experience, and maintenance. This guide will break down those differences, providing the clarity you need to choose the right two-wheeled companion for your needs. We'll simplify the jargon and give you the expert knowledge to make an informed purchase.

Kits and Custom Builds

A "bike with a motor" often refers to a project: taking a standard bicycle and adding a separate motor kit. This path is popular with hobbyists and those seeking maximum power for a minimal initial investment. These builds have deep historical roots in early motorized bicycles, which were little more than bicycles with engines attached. The appeal comes from the ability to create something unique and powerful.

Gas vs. Electric Kits

The most common kits fall into two categories. First, you have gas-powered kits, which are the classic choice for DIY builds. You'll typically find 2-stroke engines, which are simple, lightweight, and powerful for their size, but are also noisy and produce significant emissions. 4-stroke engines are an alternative, offering quieter operation and cleaner burning, but are heavier and more complex. The appeal lies in their raw power, low fuel cost, and the mechanical satisfaction of maintaining a small engine. Second, you have high-power electric kits that use electric motors exceeding the legal power limits for standard e-bikes.

In the US, this legal limit is typically 750 watts. They often feature powerful throttle-only operation, turning the bicycle into something closer to an electric moped or motorcycle. They offer silent, instant torque but come with their own set of legal and technical challenges.

Pros and Cons

Choosing the DIY route involves a significant trade-off between cost, performance, and practicality. The advantages include high customization, where you have complete control over every component, from the base bicycle to the engine and drivetrain. You also get potentially higher power since these builds are not bound by the legal speed and power restrictions of e-bikes. The initial cost is lower, as a motor kit can be significantly cheaper than a complete, factory-built e-bike. There is also the hobbyist appeal-a unique satisfaction in building, tuning, and riding a machine you assembled yourself.

However, the disadvantages are significant. The complex legal status means that in most jurisdictions, a gas-powered or overpowered electric bike is legally classified as a moped or motorcycle, requiring a license, registration, and insurance. There are reliability and safety concerns since a standard bicycle frame, brakes, and wheels are not designed to handle the stress and speed of a motor, which can lead to frame failure, inadequate stopping power, and general unreliability. These machines are maintenance intensive and require constant tinkering, mechanical knowledge, and a willingness to get your hands dirty. Gas engines are also loud and create pollutants, making them unwelcome on bike paths and in many neighborhoods.

Defining the Modern E-Bike

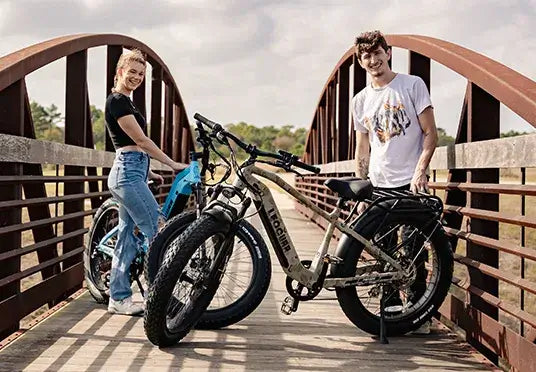

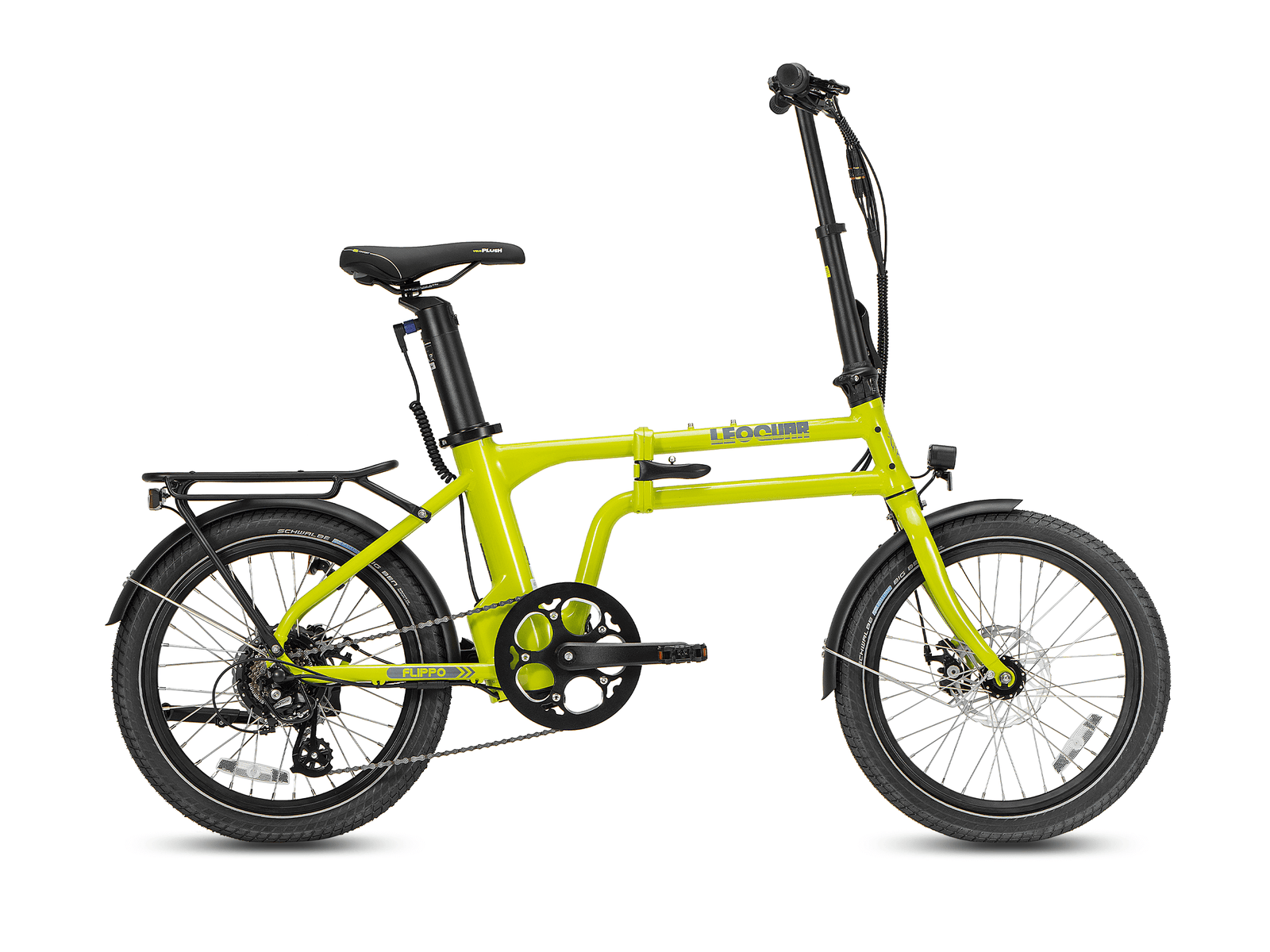

A regular e-bike is a complete, purpose-built vehicle designed and sold by a manufacturer. Unlike a kit bike, its frame, motor, battery, and components are all engineered to work together as a seamless system. These bikes are designed to be legally classified as bicycles, giving them broad access to roads and bike paths. There is a wide variety of e-bikes available, from commuters and cargo bikes to high-performance mountain bikes.

The E-Bike Class System

In the United States and many other regions, e-bikes are organized into a class system to regulate their use. Class 1 bikes have motors that provide assistance only when you are pedaling and stop assisting at 20 mph. These are the most widely accepted e-bikes, often allowed on the same paths as traditional bicycles. Class 2 bikes can have motors activated by a throttle, providing power without pedaling, but the motor assistance cuts off at 20 mph whether by throttle or pedal-assist. Class 3 bikes are like Class 1 with pedal-assist only and no throttle, but the motor assistance continues until you reach 28 mph and are typically restricted to roads and on-street bike lanes.

Understanding these classes is vital, as they determine where you can legally ride. The classification system helps law enforcement and trail managers understand what type of vehicle they're dealing with.

Pedal-Assist vs. Throttle

E-bikes deliver power in two primary ways. Pedal-assist feels like having bionic legs, where sensors detect your pedaling and tell the motor to provide a proportional boost. More advanced torque sensors measure how hard you're pedaling, delivering a very natural and intuitive feel, while cadence sensors simply detect if you are pedaling and provide a set level of assistance. Throttle systems work like the accelerator on a scooter or motorcycle, where a twist-grip or thumb-lever engages the motor on demand, whether you are pedaling or not. Many Class 2 e-bikes offer both pedal-assist and a throttle for maximum versatility.

Hub vs. Mid-Drive Motors

The motor's location dramatically affects the riding experience. Hub motors are located in the hub of the front or rear wheel and directly spin the wheel, creating a sensation of being "pushed" or "pulled" along. They are generally simpler and more affordable but can feel less natural when riding. Mid-drive motors are located at the bike's crankset where the pedals attach and apply power to the drivetrain, allowing the motor to leverage the bike's gears for better efficiency on steep hills. They also provide more balanced weight distribution and a natural riding feel that is nearly indistinguishable from a traditional bicycle.

Head-to-Head Comparison

To make the choice clearer, here is a direct comparison of the key attributes of each option.

| Characteristic | "Bike with a Motor" (DIY/Kit) | Regular E-Bike (Factory-Built) |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Classification | Typically a Moped or Motor Vehicle | Legally defined as a Bicycle (Classes 1-3) |

| Primary Power Source | Gasoline or unregulated high-watt electric motor | Regulated electric motor (e.g., <=750W in US) |

| Riding Experience | Loud, raw, mechanical. Requires active rider input. | Quiet, smooth, and integrated. Intuitive operation. |

| Upfront Cost | Lower for the kit, but requires a separate donor bike. | Higher, but is an all-inclusive, ready-to-ride package. |

| Long-Term Maintenance | High. Requires mechanical skills for engine/motor tuning. | Low. Similar to a regular bike plus battery care. |

| Where to Ride | Restricted to roads where mopeds are permitted. | Most bike lanes, paths, and roads (varies by class). |

| Safety & Reliability | Variable. Depends entirely on the builder's skill and component quality. | High. Professionally engineered, tested, and certified. |

The Legal Labyrinth

The single most important difference between these two options is their legal status. This isn't just red tape; it fundamentally dictates how, where, and if you can ride. The core question is: are you riding a bicycle or a motor vehicle?

A compliant, factory-built e-bike (Class 1, 2, or 3) is treated as a bicycle. This grants you access to a vast network of bike lanes, multi-use paths, and trails. A DIY bike with a gas engine or an electric motor exceeding legal power/speed limits is almost universally classified as a motor vehicle, like a moped or motorcycle. The consequences are significant and include licensing requirements, registration and plating, mandatory insurance, and restrictions from bike paths, sidewalks, and many park trails.

A 3-Step Legal Checklist

First, identify your bike type by asking: Is it powered by a gasoline engine? Is the electric motor rated for more than 750W? Can it provide assistance over 28 mph? If you answer yes to any of these, you are almost certainly operating a motor vehicle, not an e-bike. Second, visit your state's DMV website and use search terms like "moped definition," "motor-driven cycle," and "electric bicycle regulations" to find official government information. For a great starting point, check a resource that compiles state-by-state e-bike laws. Third, check local ordinances since your city, county, and local park authorities have their own rules for trail and path access.

Always check their websites before riding on off-road trails. Local rules can be stricter than state laws and vary significantly between jurisdictions.

The Real-World Experience

Beyond specs and laws, the day-to-day ownership experience of these two paths could not be more different. It's a tale of two very different riders with completely different priorities and skill sets.

The DIY Journey

Building a kit bike is a labor of love—and grease. The journey begins with a box of parts that may or may not include clear instructions. You'll need more than a simple Allen key set; tools like a crank puller and chain breaker become your best friends. You'll spend hours routing cables, mounting the engine, and aligning the chain sprocket.

The experience is visceral and demanding. It's the smell of gasoline and two-stroke oil, the frustration of a misaligned chain, and the scraped knuckles from a stubborn bolt. But it's also the immense triumph when the engine sputters to life for the first time. Your relationship with the bike is ongoing and requires constant attention. It demands tuning, adjustments, and a constant ear for any new rattling sounds. Every ride is a testament to your own handiwork, a raw, mechanical connection between rider and machine.

The E-Bike Experience

Buying a factory e-bike is a study in simplicity. It often arrives nearly fully assembled with clear instructions and all necessary tools included. You'll attach the handlebars, screw on the pedals, charge the battery, and go. The entire process can take less than 30 minutes and requires no special mechanical knowledge.

The experience is one of seamless integration and reliability. There's no engine to tune, no fuel to mix, and no complex maintenance schedules to follow. You press a button, and the bike works consistently every time. The motor hums quietly, the assistance feels natural, and you can focus purely on the ride rather than mechanical concerns. If something goes wrong, you have a warranty and a dealer or customer service team to call for support. It's less of a hobby and more of a transportation appliance—a dependable tool that flattens hills, shortens commutes, and expands your range with quiet efficiency.

Which One Is for You?

The choice between a DIY motorized bike and a factory e-bike comes down to your goals, skills, and tolerance for complexity. Consider what you really want from your riding experience and be honest about your mechanical abilities.

The commuter electric bike with a motor kit is for the dedicated hobbyist. It's for the person who enjoys tinkering in the garage as much as riding, who values raw, unrestricted power and total customization above all else. If you are a skilled mechanic who understands the legal implications and wants a project that will keep you busy for months, this is your path. You should also be comfortable with the legal restrictions and registration requirements that come with operating what is essentially a motorcycle.

The regular e-bike is for everyone else. It's for the daily commuter, the weekend adventurer, the parent hauling kids, or anyone who wants the benefits of a motor without the legal and mechanical headaches. If you value reliability, safety, legal access to bike paths, and a "just works" experience, a factory-built e-bike is the clear choice. This option lets you focus on riding rather than wrenching and provides peace of mind through warranties and professional support.

Before you buy, honestly assess what you want from your ride. Do you want a hobby project that requires ongoing mechanical work, or do you want a reliable mode of transport that just works? Answering that question will lead you to the perfect motorized bike for your needs and lifestyle.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can I legally ride a gas-powered bike motor on bike paths?

A: No, in most areas gas-powered bikes are classified as motor vehicles and are prohibited on bike paths, sidewalks, and multi-use trails. They typically require registration, insurance, and can only be ridden where mopeds are legally permitted, which is usually limited to roads.

Q: How much does it cost to build a bike with a motor compared to buying an e-bike?

A: A basic motor kit can cost $150-500 plus the cost of a donor bicycle, making the initial investment lower than most factory e-bikes which start around $1,000. However, factor in tools, potential repairs, registration fees, and insurance for kit bikes, which can increase the total cost significantly.

Q: Do I need a license to ride an e-bike?

A: For Class 1, 2, and 3 e-bikes that meet legal power limits (typically 750W or less), no license is required in most areas since they're classified as bicycles. However, DIY bikes with gas engines or high-powered electric motors usually require a driver's license and sometimes a motorcycle endorsement.

Q: Which type of bike with a motor is more reliable?

A: Factory-built e-bikes are generally much more reliable since they're professionally engineered and tested as complete systems. DIY motor kits depend heavily on the builder's skill and the quality of components used, often resulting in more frequent breakdowns and maintenance needs.

Q: Can I convert my regular bicycle into an e-bike legally?

A: Yes, you can legally convert a regular bicycle using an electric motor kit as long as the final result meets e-bike regulations (typically 750W or less, speed-limited to 20-28 mph depending on class). Gas conversions or high-powered electric conversions will likely be classified as motor vehicles requiring registration.

Leave a comment